An Asian American Christian legacy story

November 21, 2021. Stop AAPI Hate is one of the most significant movements today. Co-founded by Prof. Russell Jeung (one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people of the world for 2021), it and the AAPI community have drawn more attention to anti-Asian discrimination than at any moment in U.S. history. But it wasn’t the only time that the AAPI community rallied to fight anti-Asian discrimination and violence. And it wasn’t the first time that Asian American Christians joined the struggle. This post draws from a chapter of my forthcoming book on the history of Asian American Christianity.

When Vincent Chin was bludgeoned to death by Ronald Ebens and his stepson, laid-off autoworker Michael Nitz, on June 19, 1982, the lenient sentence re-ignited the Asian American movement. The earlier phase of the movement centered on universities and local community empowerment. This time, it was a broad-based, nationwide movement that focused on anti-Asian violence and stronger federal hate crime legislation.[1]

In San Francisco’s Chinatown, Rev. Norman Fong was among the community leaders who rallied the Asian American community to respond to the verdict. Representatives from Chinatown churches, the Asian Law Caucus, and other community groups met at Cameron House in the summer of 1983 and formed Asian Americans for Justice (AAJ), which was modeled after Detroit’s American Citizens for Justice. AAJ member Hoyt Zia – Helen Zia’s brother – helped synchronize with the Detroit movement. Fong, who served as secretary for AAJ, had dedicated himself to activism when his family was evicted from their Chinatown home in 1970. Support from the Presbyterian Church in Chinatown and Cameron House enabled his family find housing again. Cameron House and the Presbyterian Church in Chinatown played pivotal roles in mobilizing the community to fight for affordable housing.

Rev. Fong’s direct experience of the vulnerability of immigrant communities in the face of housing shortage in Chinatown encouraged him to become a community organizer. Under the leadership of his longtime mentor Rev. Harry Chuck, Fong organized disempowered youth and seniors. This led to his call to ministry and decision to study at Princeton Theological Seminary, where he chaired its Social Action Committee and studied Liberation Theology. After a stint as a Mission Intern in Hong Kong and the Philippines, he returned to San Francisco in 1979 even more determined to support Chinese immigrants. He finished up his M.Div. at San Francisco Theological Seminary, joined Cameron House’s Youth Ministries Team and served as a pastor at the Presbyterian Church of Chinatown.

In 1983, a few of the members of AAJ were involved with Rev. Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition. Jackson had decided to run for U.S. President that fall and became aware of Asian American protests against the verdict. Chin’s grieving mother, Lily Chin – the face of the movement – was invited to San Francisco to mobilize the community during the second anniversary of Chin’s murder in June 1984. Jackson joined her in a press conference at Cameron House, which drew the attention of the media. “Every Chinese media covered it, too,” Fong recalled. “It brought together the whole community, not just the activists…it was a pivotal moment here in the Bay Area.” The press conference was followed by an impromptu march through Chinatown. “As I led the march through Chinatown, I held a box to collect for the Vincent Chin Legal Defense Fund,” Fong noted, “I was so touched by every storeowner, even seniors on the street – everyone donating. Total unity in a sometimes divided community.” Over $20,000 was collected for what would become the biggest movement he was ever a part of. Fong contacted other churches in Chinatown and the S.F. Bay Area and Asian American caucuses. “We got great responses from every caucus and denomination,” he noted. There was much needed “solidarity with Jewish, Black, and Latino communities.” [2]

According to Harry Chuck, Fong was a key catalyst for Presbyterian Church in Chinatown’s engagement in the Vincent Chin case. “Norman provided the impetus (and exuberance) for our participation and support of the Vincent Chin case. At the time, our clergy staff resided at Cameron House so we were able to dedicate office and meeting areas for organizing community support.” [3]

Reverends Norman Fong and Jessie Jackson at the June 2021 Rally in Chinatown: “Solidarity in the Struggle from Vincent Chin to George Floyd.” Norman still works part time for the Chinatown Community Development Corporation. [photo credit: Norman Fong]

At the same time Rev. Dr. Wesley Woo, also a product of Cameron House, was a year into his appointment as Associate for Racial Justice and Asian Mission Development in the United Presbyterian Church’s Department on Racial Justice. Having just completed his Ph.D. at the Graduate Theological Union, Woo had dabbled with pursuing an academic career. He taught courses at the GTU and U.C. Berkeley and volunteered with PACTS while working on his doctorate. His dissertation, Protestant Work Among the Chinese in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850-1920 (1983) was the first historical study of an Asian American Christian community. But ministry and community organizing commitments encouraged him to pursue denominational and ecumenical leadership roles where he felt he could make a larger impact. After serving as interim Associate for Asian Missions Development for the United Presbyterian Church, he took on a part-time role as Secretary for Pacific Asian American Ministries in the Reformed Church in America which allowed him time to defend his dissertation.

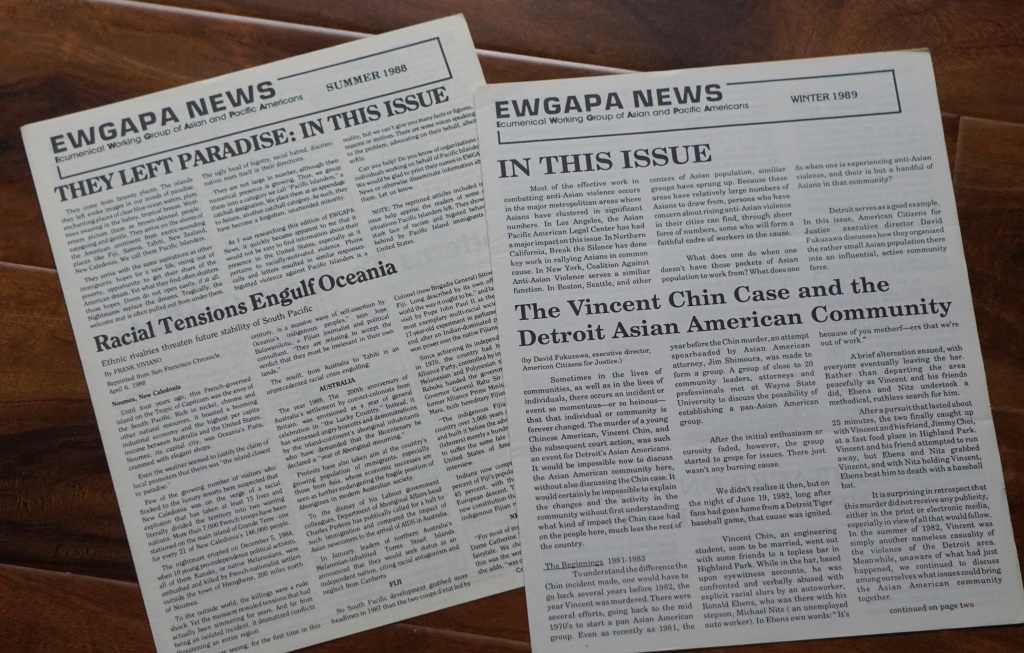

When he assumed the Associate for Racial Justice and Asian Mission Development, one of his first actions was to respond to the Chin verdict and concerns about anti-Asian racism. He reached out to American Citizens for Justice, visited leaders like Helen Zia and Jim Shimoura in Detroit, and developed close working relationships with them. He also put his community organizing skills to practice by networking with other Asian American denominational leaders and activists. This resulted in the formation of the Ecumenical Working Group of Asian and Pacific Americans (EWGAPA) in December 1984. Nine denominations and three community groups attended the founding national consultation in San Francisco, namely, the American Baptist Churches, Episcopal Church, Friends, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Presbyterian Church (USA), Reformed Church in America, Lutheran Church of American, United Church of Christ, United Methodist Churches, American Citizens for Justice, Asian Pacific American Legal Center, and AAJ. By including non-religious community groups into the network, Woo was able to develop strong working relationships with Helen Zia, Steward Koh, and others. “I wanted to say that churches are concerned about anti-Asian violence and want to be part of [this cause],” Woo recalled. The group met two or three times a year to monitor the Vincent Chin case and other incidents of anti-Asian discrimination.[4] EWGAPA’s mission was to “focus attention of churches on anti-Asian violence” and identified four purposes:

- Serve as a form for information sharing, networking, and support (including publishing a newsletter three times a year)

- Raise the consciousness within churches, both denominationally and locally, to racially motivated violence against Asians and Pacific Islanders in the U.S.

- Support communities and groups combatting anti-Asian violence.

- Facilitate dialogue with other racial ethnic groups seeking to end violence and racism.

Woo drafted a “Background Statement and Resolution on Racially Motivated Violence Against Asians in America,” which was adopted by the 1985 General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA). In it, the denomination resolved to “declare its opposition to racially motivated violence in any form and calls upon all Presbyterians to speak out against this sin.” Other mainline Protestant denominations followed suit.

Woo’s close friend, Rev. Dr. Wally Ryan Kuroiwa, then with the Disciples of Christ, spearheaded many of EWGAPA’a activities. This included the EWGAPA News, which reprinted articles documenting and monitoring incidences of anti-Asian violence and hate crimes. EWGAPA also produced study guides “It’s Just Not Fair…” Racially Motivated Violence Against Asians in the United States (June, 1989) and Beyond the Crucible: Responses to Anti-Asian Hatred (1994). Hawaii-born Kuriowa converted to Christianity in college by Southern Baptist campus ministers. Later, he found his way into the Disciples of Christ and finally, the United Church of Christ, where he felt most at home theologically. He earned his Th.D. at Chandler School of Theology and was a pastor of a Disciples congregation in Ohio when he got involved with EWGAPA.

“It’s Just Not Fair…”, the title of the first study guide, were Vincent Chin’s dying words. In it, Kuriowa places the issue of anti-Asian violence within a historical context, demonstrating that its root causes were not new. He then shows that economic factors were among the most important causes for anti-Asian violence. The rise and proliferation of hate groups and persistent stereotypes of Asian Americans constituted other factors. Kuroiwa then provides additional contemporary case studies of anti-Asian violence to show that Vincent Chin’s murder was not an isolated case. Thirdly, he offered some biblical theological reflections to critique racism by centering the gospel narrative of Jesus’ life and teachings, giving particular attention to the image of Jesus’ suffering servanthood, and casting a vision of all humankind as part of God’s family. Finally, Kuroiwa recommends community organizing as a way to address immediate crises and suggests three long term solutions: education, a national system to monitor incidents of anti-Asian violence, and AAPI networking.[5]

Even Renee Tajima-Peña’s 1989 Academy Award–nominated documentary, Who Killed Vincent Chin? had a touch of mainline Protestant Asian American influence! Wesley Woo’s office was the first to provide financial support for the film. Christine Choy, the co-director of that film, later told Wesley that “the initial funding made it easier or possible for her to approach others to invest in that project.”

Renee Tajima-Peña herself was raised in a Presbyterian family. Her parents attended the Altadena First Presbyterian Church in Los Angeles which was pastored by her uncle, Donald Toriumi. Her paternal grandfather, Kengo Tajima, came to the United States because of religious persecution in Japan, studied theology at Yale and the University of California at Berkeley, and spent some time as a circuit-riding preacher in places like Provo Canyon, Utah, ministering to Asian railroad workers before becoming a pastor of Japanese American churches in Los Angeles. She reflected

If I look back on my life, I can see how at each critical juncture—the decision to become a student activist, a media activist, marrying outside of my race, loving and sacrificing for my son, foregoing certain material rewards, trying to be a mensch, has been a function of Christian values I learned at home—the perception of injustice and inequality, and the responsibility of the individual to work collectively for social change.

– Rita Nakashima Brock and Nami Kim, “Asian Pacific American Protestant Women” [6]

The coalition of Asian American community activists and denominational leaders succeeded at drawing attention to the rise of anti-Asian violence and successfully advocated for the passage of the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990 and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The former required the Attorney General to collect data on crimes committed because of the victim’s race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity while the latter increased the penalties for hate crimes. In the backdrop was the 1992 Los Angeles uprising where more than 2,500 Asian-owned (mostly Korean) businesses were damaged or destroyed. For the first time Asian immigrants and Asian Americans were placed at the center of a new public conversations about multiracial America. EWGAPA, having recognized how “deep, pervasive, and institutionalized within the social order” anti-Asian racism was (as well as racism directed to other people of color), now sought to highlight stories of “creative struggles, defining moments, and positive actions.” Thus, Beyond the Crucible: Responses to Anti-Asian Hatred (1994) was written to offer case studies of APA communities that have “responded with positive actions to anti-Asian racism and violence.”[7]

Beyond the Crucible highlights examples from community organizations such as the Council of Asian American Organizations in Houston, Texas, Asian Americans United in Philadelphia, and the Committee Against Anti-Asian in New York City. Other grassroots efforts in Orange County, Fountain Valley, and San Francisco, California were examined. Featured also were case studies of mediation and alliance building between Koreans and African Americans in Chicago, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles. One study explored the University of California at Irvine students strike for Asian American studies. Taken together, all these case studies highlighted the growing Asian American diversity; Koreans and Southeast Asians were now prominently featured. Sandwiched around these case studies were two articles by AsianWeek staff writer, Samual R. Cacas. The first was a progress reports on the 1993-94 federal legislation on hate crime law and the second featured the National Asian Pacific-American Legal Consortium’s report on the data of anti-Asian violence. Katy Imahara provided an analysis that inked anti-immigrant sentiment to anti-Asian violence. But two key articles offered important theological and ministry reflection. Roland Kawano’s meditation on religion in the ethnic community as a significant resource for grieving and healing gave justification for the importance of religious and theological reflection in the struggle for Asian American empowerment. Franco Kwan, an Episcopalian priest based in New York City, concluded Beyond the Crucible with recommendations for “Building a Social Justice Ministry.”

EWGAPA ceased operations in the mid-1990s in the face of declining mainline Protestant fortunes. While mainline Asian American Protestants have continued to address anti-Asian racism, such efforts never again reached the national level led by Woo, Kuroiwa, and their fellow ecumenical leaders. In a recent conversation, Kuroiwa told me that he didn’t think EWGAPA made significant headway into the Asian American Christian community – especially when compared with the social media savvy of Stop AAPI Hate. Furthermore, in the 1980s, immigrant Asian American congregations experienced explosive growth but did not identify strongly with mainline denominations, despite the efforts of American-born or raised mainline Protestant Asians like Woo and Kuroiwa. Most post-1965 Asian American Christians preferred ethnic independency or chose to partner with conservative evangelical networks and denominations, and were invisible in this fight against AAPI hate.

For his part, Dr. Kuroiwa counts as one of his happier ministry achievements the successful efforts in 1993 to petition the United Church of Christ to issue an apology for the actions of the Hawaiian Evangelical Association (which later became the Hawai‘i Conference United Church of Christ). The Association had participated in the illegal overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani a century earlier. In 1996, the Hawaiian Conference provided redress to the Native Hawaiian churches. [7]

The public witness of Cameron House, Norman Fong, Harry Chuck, Wesley Woo, Wally Kuroiwa, Renee Tajima-Peña, EWGAPA, Jesse Jackson, and many others should not be forgotten. Indeed, their effort was one of the fruits of the Asian American caucus movements of the 1970s.

This coalition of Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and other American-born Asians within mainline Protestantism defined Asian American Christianity. More than a people group to target for evangelism, Asian American Christians also sought to free Christianity from its Euro-American socio-political and cultural captivity. In so far as they have given voice to the concerns of Asian Americans, they have pressed American Christianity forward to fulfill its multiracial kingdom promise. This little known story of Christians who spoke out against anti-Asian violence in the wake of Vincent Chin is an Asian American Christian legacy.

Notes

[1] Helen Zia, Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000).

[2] Norman Fong interview with Tim Tseng (September 17, 2021) and email to Tim Tseng (November 11, 2021).

[3] Harry Chuck email to Tim Tseng (November 11, 2021).

[4] Wesley S. Woo, Protestant Work Among the Chinese in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850-1920 (Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA: 1983). Wesley Woo interview with Tim Tseng (September 16, 2021) and email to Tim Tseng (November 11, 2021).

[5] Wallace Ryan Kuroiwa and Victoria Lee Moy, “It’s Just Not Fair…” Racially Motivated Violence Against Asians in the United States (EWGAPA: June, 1989); Brenda Paik Sunoo, Beyond the Crucible: Responses to Anti-Asian Hatred (EWGAPA, 1994).

[6] Rita Nakashima Brock and Nami Kim, “Asian Pacific American Protestant Women,” in Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Volume 1 (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006), pp. 498-505.

[7] Ed Nakawatase, “Introduction,”Beyond the Crucible: Responses to Anti-Asian Hatred edited by Brenda Paik Sunoo (EWGAPA, 1994), 2-3.

[8] Wallace Kuriowa interview with Tim Tseng (October 3, 2021); “Apology and Redress” Hawaiian Conference, United Church of Christ. Access at https://www.hcucc.org/apology-redress

You must be logged in to post a comment.