These remarks were given at the Asian American Christian Collaborative’s Faith and Politics Forum on July 31, 2024. – Tim

Whenever Christians gather for worship or fellowship, we reaffirm our identity and calling in Christ. And when we do that, we are passing down a heritage of faith. But what is the content of that heritage? We know that it is about memories of Jesus and his on-going work through the Holy Spirit today. But does the tradition also include our cultural and historical experiences? Or are we passing down a tradition that excludes or erases Asian American realities? And even if we wanted to include the Asian American experience, what is that experience anyway? We didn’t just fall out of a coconut tree, did we?

I want to suggest that Asian American heritage doesn’t exist until the history is told or written. It doesn’t exist until the history is received by and transmitted to people today and passed along to the next generation. In fact, attempts to affirm history-less Asian American identities are like trying to keep cut flowers alive. Unless the roots are planted in fertile soil, it’s an impossible task. Our histories are our roots and they need to be nourished in good soil. According to historic Christian orthodoxy, God created the world good – and this includes human history. So despite the fallen nature of creation and history, the instinct to cut off our roots and avoid touching “unclean” soil is actually a gnostic impulse.

So tonight, I invite you to do a little planting with me, that is, do a bit of history making with me.

But first, it’s important to note that political engagement is just one aspect of the history of Asian American Christianity. Evangelism, missions, church planting, and theological development are also part of the larger history – a story of our quest for a better country.

Secondly, with regards to political engagement, I want to describe two Asian American Christian historical contexts before sharing five brief stories: the undergirding biblical theology and the political mobilization dilemma that Asian American Christians embraced and faced. These contexts may differ from our contemporary situations, but I believe that being aware of them can help us discern how to navigate the current political environment, discern the future of Asian American Christian political engagement, and even cultivate healthier Asian American faith communities.

Undergirding biblical theology

As I looked at Asian American Christians who have engaged politics, two dimensions of their biblical theology stand out. First is the idea that the gospel is salvation for soul AND society. Over the years, different labels have been used to describe this biblical theology: postmillennial evangelicalism, social gospel & liberalism, neo-orthodoxy & liberationist. When politically engaged Asian American Christians read scripture and reflected on their socio-political contexts, they started with the premise that God redeems individual souls AND social structures. Most Asian American Christians prioritized the salvation of the individual soul but none considered God’s world irredeemable. Theirs was not a life-boat theology. This biblical theology yielded more porous boundaries between church and the outside community than fundamentalism did and gave Asian American Christian permission to collaborate and build coalitions with non-Christians.

Second, they identified the Kingdom of God or the Christian social order with modern liberal democracy. They saw the feudal past, whether Roman Catholic Western Europe or pre-modern Asian societies, to be backward. They did not believe that theocracy or empire was what Jesus envisioned. Democracy, on the other hand, represented a progressive vision of expanding human rights, social justice, and international peace – all of which they found in the Christian gospel. They acknowledged that modern democracy was not perfect, but Christian discipleship included working towards the realization of democracy, whether it be racial, economic, gendered, or international.

The political mobilization dilemma

Politically engaged Asian American Christians were also focused on the very practical concerns of their communities. Facing an America that was hostile towards Asian Americans, they needed to stop laws and policies that harmed their communities. They needed to enact laws and policies that would give their communities voice and place in America. Since Asian Americans made up such a small percentage of the U.S. population, and since Asian immigrants were not allowed to naturalize until 1952, they did not have access to the traditional means of engaging the political process. They did not have big money influence like a John D. Rockefeller. They did not have relational influence like many white Protestant pastors and church leaders who were related to important political leaders. They did not have a large enough constituency like white Protestants, who had accrued significant electoral power over the years.

But Asian American Christians still engaged politics, albeit through access to white missionaries and church leaders. Thus, they made alliances with Protestants who shared their interests and faith. Of course, this also created adjacency dependency. But through white Protestant surrogates, Asian Americans pressured government officials to support their interests even though they usually lost. This alliance also allowed them to use the justice system to defend their rights. A surprising number of cases litigated by Asian Americans resulted in the expansion of civil rights for everyone. Finally this alliance gave Asian American Christians confidence to mobilize their communities to discern, engage, and rally their communities to support or oppose important issues.

Asian American issues in history

Let us look at a few examples of political engagement. I highlight five issues that Asian American Christians engaged – accompanied by examples of Asian American Christians who engaged them. I deliberately chose these examples because they all have Wikipedia entries and are easy to access. In most cases, the Christian faith of these important individuals is not given much attention – which cries out for more research in Asian American Christianity.

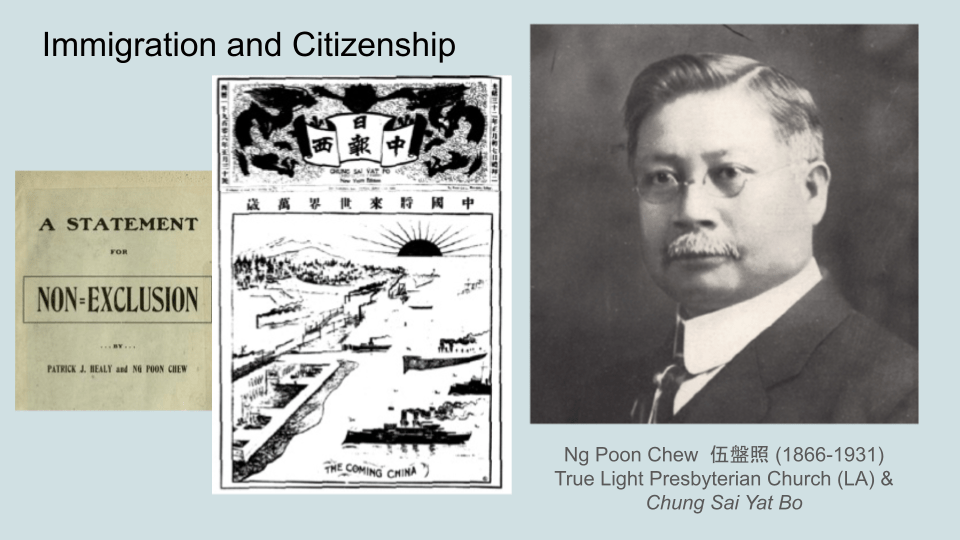

(1) Immigration and citizenship

Between 1882 and 1934, Chinese and other Asian laborers were not permitted to migrate or naturalize. Exclusionary Immigration and Alien Land Laws were established on the basis of ethnicity, race, and class even though many of them did not explicitly mention race or ethnicity. Christian leaders like Ng Poon Chew 伍盤照 (1866-1931) attempted to sway public opinion away from the dominant anti-immigration nativism. Ng came to the U.S. before the 1882 Chinese exclusion act, converted to Christianity, and then received a call to ministry. He went to San Francisco Theological Seminary and pastored the Chinese Presbyterian Mission in Los Angeles (now True Light Presbyterian Church). He felt called to journalism and left the church to publish the influential Christian newspaper, the Chung Sai Yat Bao. Ng also went on lecture circuits and wrote extensively. His mission was to educate Americans about the Chinese, protest Chinese exclusion, and support revolutionary democracy in China. He was also known as the the Chinese Mark Twain

(2) Asian Christian nationalism. E.g., Korean Independence

Philip Jaisohn 서재필 (1864-1951), Korean American politician and physician advocated for Korean national independence from Japanese occupation. Like many of his peers, who opposed colonialism and imperialism, he embraced democracy in Asia. He was the first Korean to become a naturalized citizen of the United States. He founded the Tongnip Sinmun (the Independent), the first Korean newspaper written entirely in Hangul and helped organize the First Korean Congress in Philadelphia a little more than a month after the March 1, 1919 movement in Korea. Jaisohn was an admirer of American-style liberalism and republicanism which he connected to Protestant Christianity. He was also reform-minded, and sought to revise Confucianist culture and institutions in Korea.

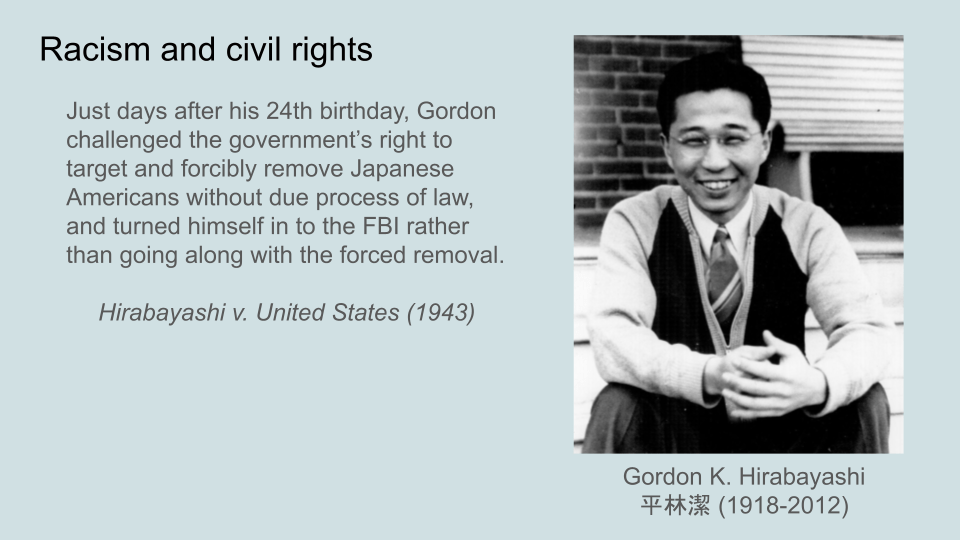

(3) Racism and civil rights.

There were many Asian American Christians who supported the Civil Rights Movement, but I’ll select the one who fought for Asian Americans. Gordon K. Hirabayashi 平林潔 (1918-2012) was an American sociologist who taught in Canada. He is best known for his Christian principled resistance to the Japanese American internment during World War II and the court case which bears his name, Hirabayashi v. United States (1943). He was born in Seattle to a Christian family who was associated with the Mukyōkai Christian Movement (Uchimura Kando’s “no church movement”). In 1937 he went to the University of Washington where he participated in the YMCA and became a religious pacifist. He joined the Quaker-run American Friends Service Committee. He was one of three Japanese American to openly defy the internment camp curfew order in 1942. The other two were Fred Korematsu and Minoru Yasui. Like Hirabayahsi, Korematsu was an active Christian who was a member and Elder of the First Presbyterian Church of Oakland after World War II.

“Just days after his 24th birthday, Gordon challenged the government’s right to target and forcibly remove Japanese Americans without due process of law, and turned himself in to the FBI rather than going along with the forced removal.” Hirabayashi’s challenge was motivated by a desire to challenge the legality of the internment camps. This led to Hirabayashi v. United States (1943) case. The Supreme Court ruled against him and sent him to prison to serve 90 days. He also refused induction into the military as a conscientious objector and was imprisoned again.

After the War, he became a sociology professor at University of Alberta (Canada) and was an active member of Canadian Yearly Meeting of the Quakers and continued to support human rights issues. Shortly after his retirement in 1983, his case was reopened. Both convictions were vacated. It took 40 years to correct this injustice. “There was a time when I felt that the Constitution failed me,” Gordon stated after his convictions were overturned. “But with the reversal in the courts and in public statements from the government, I feel that our country has proven that the Constitution is worth upholding. The U.S. government admitted it made a mistake. A country that can do that is a strong country. I have more faith and allegiance to the Constitution than I ever had before.” [Quotes from “Happy 100th Birthday, Gordon Hirabayahsi!“]

(4) Community and women empowerment

Of the three women featured on this slide: Dr. Mabel Lee 李彬华 (1896-1966), Yuri Kochiyama ユリコウチヤマ (1921-2014), and Alice Fong Yu 尤方玉屏 (1905-2000). I’ll focus on Alice Fong Yu. Alice grew up in Vallejo where her family joined white Presbyterian church. Her Christian upbringing encouraged her and her 5 sisters to get an education. Her parents also encouraged her to be a teacher. It was unusual for Chinese families at the time to be support education and public vocations for their daughters. Alice became the first Chinese public school teacher in America and taught at a public school in S.F. Chinatown. But she also became an influential community organizer and activist. The origins of her activism are also rooted in Christian faith. As a teenager Alice was involved with the YWCA Girls Reserve and earned a reputation of being a great fund raiser. In college, she and six friends from the Chinese Congregational Church of San Francisco started the Circle and Square Club. Circle and Square mobilized Chinese American women to support China during Sino-Japanese conflict, and care for orphans, elderly, and the poor in Chinatown, and engage in voter registration. Alice was also very invested in the Chinese YWCA and directly empowered Chinese young women through workshops, bible studies, and community projects. Finally, Alice Fong Yu was one the three American Born Chinese to start the Chinese Christian Lake Tahoe Youth Conference (f. 1933), which for thirty years gathered Christian and non-Christian young adults to engage Christian faith and social issues of the day.

(5) Anti-Asian violence: Responding to the Vincent Chin murder. 1980s

Finally, when Vincent Chin was murdered in 1982, and the judge in his case allowed the accused murderers to go free, a new wave of Asian American activism was unleashed. Asian American Protestant leaders worked at building coalition with activists and attempted to mobilize the Protestant churches to speak out against anti-Asian racism and anti-Asian violence. Among the most notable leaders were Rev. Dr. Wesley Woo, Rev. Wally Ryan Kuroiwa, and Rev. Norman Fong (see my blog “Before Stop-AAPI hate, there was EWGAPA“). Woo was a national executive in the Presbyterian Church, USA national office in the mid-1980s. He had experience as a pastor with community organizing training and was a historian. During the movement for Vincent Chin, he and Wally Kuroiwa mobilized Asian American leaders from other Protestant denominations to form the Ecumenical Working Group of Asian Pacific Americans (EWGAPA) to monitor instances of anti-Asian violence and to persuade their denominations to issue statements and resolutions against anti-Asian violence. EWGAPA also collaborated with Asian American activists. Woo’s office helped fund René Tajima’s documentary “Who Killed Vincent Chin” (Tajima’s relatives are pastors and church leaders at Altaden Presbyterian Church). As for Rev. Norman Fong, a long time youth and young adult pastor with a passion for SF Chinatown’s social problems, the Vincent Chin case inspired him to mobilize the local Asian American Christian community in the S.F. Bay Area. He befriended the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who was the first public national figure to speak out for Vincent Chin. During his presidential campaign, Jackson came to Cameron House to speak in support of Lily Chin’s drive for justice for her son.

Conclusion

These are just a few examples of the many Asian American Christians who felt compelled by their faith to be involved in the American political process on behalf of their people. The lens of “secular” historians views these individuals as heroes who promoted the American dream of prosperity and inclusive democracy for Asian Americans. But I argue that they were really members of “the great cloud” of Asian American witnesses (Heb. 12:1) whose faith gave them a “longing for a better country — a heavenly one” (Heb. 11:16). Because the American dream was “not worthy of them” (Heb. 11:38), they aspired to make America and the world a better place.

Discussion

- How did the political engagement of previous generations of Asian American Christians differ from the kind of engagements we see today?

- Should Asian American congregations and parachurch organizations be sites for political mobilization? Why or why not?

Leave a comment